More from The University of Texas

Plus, debate me. Plus, a Tweet and 800 million points. Plus, spy glasses in Japan.

Issue 296

Subscribe below to join 3,865 other smart people who get “The Cheat Sheet.” New Issues every Tuesday and Thursday.

If you enjoy “The Cheat Sheet,” please consider joining the 18 amazing people who are chipping in a few bucks via Patreon. Or joining the 37 outstanding citizens who are now paid subscribers. Paid subscriptions start at $8 a month. Thank you!

More from Texas

In March, I wrote about the absurd policy at The University of Texas, Austin regarding the school’s consistent and demonstrated disinterest in academic integrity.

In that piece I wrote:

All in all, given the evidence we saw in the school’s numbers during the pandemic, given its decision to avoid proctoring its online assessments, given its decision to turn off AI detection — it’s clear to me that UT Austin simply does not care about protecting its academic integrity. Or, honestly, care to even know how big a problem it has.

Then, maybe ten days ago, I wrote an article for Forbes on an issue that worries me — that schools allowing, even encouraging, students to use AI today are setting students up for accusations of cheating later, as their careers bloom and they acquire positions of authority or influence. I really do believe that’s going to be a problem.

In that Forbes piece, I mention that the policies at Texas in particular strike me as odd because the school fought for — and won — the ability to revoke awarded degrees when evidence of academic misconduct is discovered (see Issue looks like I forgot to number this one).

To me, this feels like a slippery rock to try to stand on — not actively inquiring about misuse of AI today, while being able to revoke a degree for it later.

Anyway, in advance of the Forbes article, I asked UT if it wished to comment on the question. And while I used some of the school’s reply in that article, I could not use all of it — mostly because it was unresponsive.

Before I share the full statement from the school below — which they gave permission to do — I am aware of a power imbalance here. The school is commenting on the record, to a more or less blank page, while I get far more time and space to dissect it, and where I think it deserves it, comment. That’s unfair.

So, I make this offer — should someone at UT wish to engage with me on these issues, in public, in a fair and respectful dialogue, I am in. I think several of the school’s policies beg for direct challenge and the school absolutely deserves the ability to defend them, or to challenge my views, on more or less equal footing. So, if the school will set it up, I’ll pay my own way.

(Not that this will happen or that there’s any utility in waiting, but the Gators face the Longhorns in Austin on November 9, so anytime around that weekend could work.)

Fun aside, my offer is sincere.

The full statement, attributed to Art Markman, Vice Provost for Academic Affairs at the University of Texas, Austin is:

Thanks. This misses our global strategy.

AI detectors are not particularly accurate detectors of text that has been generated with AI, and so we are more likely to clog our system with false accusations than to catch people using AI inappropriately.

In addition, we released a new version of our honor code earlier this year. The aim was to focus students on ‘the intentional pursuit of learning and scholarship.’ Our aim is for students to recognize that the purpose of assignments is not to create the product, but to learn the skill. We have created lots of resources around developing authentic assessments and to help move us away from simple assignments for which an essay turned in using a large language model would be sufficient.

Finally, we have worked hard to incorporate AI into assignments so that students have an opportunity to learn to use AI tools as part of their work and to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of LLMs as a tool.

Keep in mind that my article was about the inconsistency of turning off AI detectors while fighting for the ability to revoke degrees for cheating, and the bind in which that could place thousands of students and the university. So, I got nothing on that.

And while the comment begins with “global strategy,” Markman does not share what higher purpose is served by not knowing who is or is not actually doing the work to earn a degree. That’s too bad, because whatever strategic goal exists at the end of knowing less about student work, I’m really interested in hearing it.

Markman also says AI detectors are “not particularly accurate.” Which means he has either missed or misread the abundant evidence to the contrary. Every single study that has tested credible AI detection systems shows them to be remarkably accurate. The system that the University of Texas unplugged has, without exception, tested in the top two or three most accurate systems on the market.

Giving the benefit of the doubt, some detectors may be inaccurate. And they are. I’ve written many times how several are complete junk. But we’re not in an abstract setting in this conversation. The University had a named system, one that has been tested and tested well. The school shut it down.

In the next line, I think we get an accidental admission about AI detectors clogging the school’s system. To me, this says a ton — that the concern is about administrative burden, not integrity.

Markman does say that, in his view, the system will clog with false accusations although there’s no justification for this. As mentioned, good AI detectors are highly accurate, with “false positive” rates (a false indication of AI text), around 2%. Only in a world in which an overwhelming number of students are having work flagged for probable AI use, would 2% clog anything. Maybe, if AI flags are gunking up your system, and your system is what you’re worried about, concentrate on the 98%. Just an idea.

Moreover, and most importantly, this idea that “false accusations” will clog the school’s systems assumes that a flag of AI similarity leads directly and inexorably to a formal citation and review — as if faculty cannot or will not exercise any judgement or review at all. I remain baffled as to why administrators think so little of their faculty on this issue, that they see them as mindless robots who will do nothing except: see flag, file report. Beep, beep, bop.

I’m not a teacher and even I’m offended.

Boiling that down, the only scenario in which a system would be clogged with false accusations is one in which nearly every student was being flagged and every flag resulted in an administrative case.

But there is one sure-fire way to be sure your review system is clog-free. Don’t check. If you don’t know, you can’t be expected to act.

Here’s where I remind you that in 2021, the University of Texas issued a report showing that during the pandemic, in the zenith of remote learning, the school’s remote proctoring system flagged 27 cases of suspected cheating (see Issue 282). Total. The system was suspected of being inaccurate, so the school suggested not using it.

So, when remote proctoring was not catching cheating, the school moved away from it. When the school is worried that AI detection will catch too much suspected cheating, the school moved away from it. Seems that, whatever the challenge, Texas has the same solution — just turn it off.

Let me also comment on the fabulously absurd idea that using the AI detection system that Texas could be using is “more likely” to return “false accusations than to catch people using AI inappropriately.”

There is no place in the physical reality that we share on this planet in which that is true. None. There is actual data to overwhelmingly disprove this. Open question — is there any data anywhere showing that Turnitin’s AI detection system is more likely to spin up a false positive than a true positive? Any at all? If you think you have it, I beg you, send it to me.

Finally, honor codes and “developing authentic assessments” — the warm blankets and lullabies of academic integrity. They sound great, but afford as much insulation against academic misconduct as, well, warm blankets and lullabies. That’s especially true if they are all you have.

And I am glad that, at Texas, the “aim is for students to recognize that the purpose of assignments is not to create the product, but to learn the skill.” That’s great. I think, however, that such an aim is neither unique nor effective. Every school and every teacher aims to have students recognize and embrace learning goals over products and grades. It is — how do I put this? — not working.

Finally, I must note with added bewilderment the Provost’s statement that Texas has, “worked hard to incorporate AI into assignments so that students have an opportunity to learn to use AI tools as part of their work.”

If you recall from like an hour ago, this was the very problem I was trying to address in Forbes. Namely, how incorporating AI in student work, especially with little or no oversight regarding ethical or approved use, is setting students up for public, highly consequential accusations later. That future allegations of misconduct would be very difficult to judge and, with the University being able to act, it may be expected to. Which, if you’re worried about systems, that is going to be a very public, very sloppy, very heated clog.

All of which probably leaves us where we started — that I have no idea what school leaders at the University of Texas are doing. Or why.

Though I do recognize, if making life easy on administrators is the goal, turning off all your cheating prevention and detection systems will do the trick. But if the goal is ensuring student learning and/or the value of a degree, it won’t.

A Tweet and 800,000,000 Points

A few days ago, a Twitter (X) user posted an item you should see and, ideally, absorb.

If you cannot see it or access it, the post says:

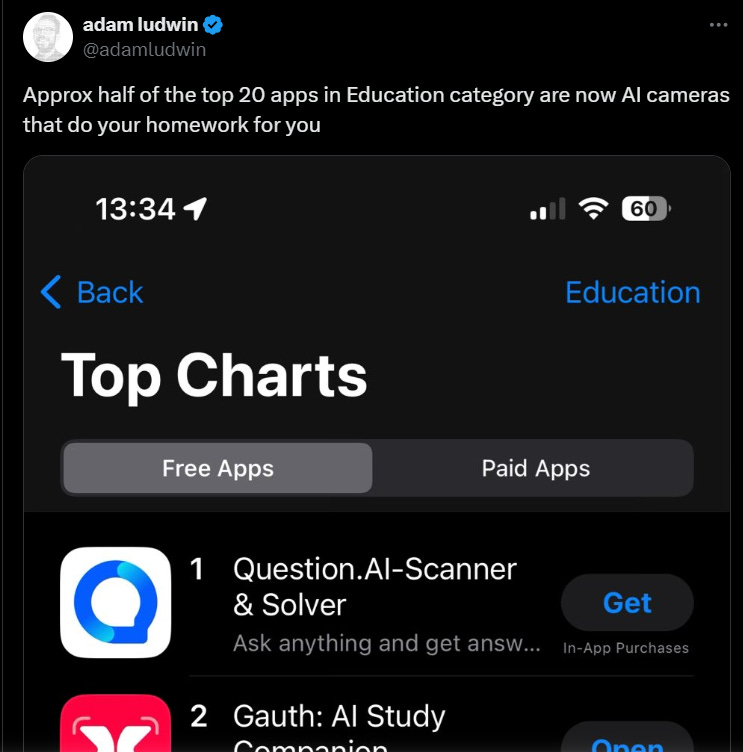

Approx half of the top 20 apps in Education category are now AI cameras that do your homework for you

As far as I can glean, the poster has no particular background or affiliation with academia or academic integrity. I am also not entirely sure what his point is. But it doesn’t matter — at least not to me.

What he said is right. Some of the most popular apps in “education” are apps that are designed and sold to spit out answers to homework or test questions. They use a smartphone camera to read the question and provide an on-screen answer instantly — no sharing questions, no asking an expert cheater, just immediate answers with little to no data fingerprints.

Worse, the apps that specialize in math can provide the step-by-step solutions instantly, on screen, so simple copying can provide fabricated evidence of actual work.

The point — my point — is that we are in an era where cheating is universally available and used at nearly incomprehensible scale.

For context, Duolingo, the language learning app, is listed as the third most popular education application, behind two “problem solver” and “AI study companion” offerings. Duolingo has more than 800,000,000 downloads. In 2021, leaders at Photomath, number four on this list of “education” apps, told me their instant answer math app had more than 250 million downloads. Again, that was three years ago.

For those who care about such things, the ubiquity of these kinds of cheating apps means that any academic assessment in which a) there are correct answers and b) students are not observed is c) almost certainly compromised. And we’re not even counting student collusion or the older, slower cheating services such as Course Hero and Chegg.

And while I have you here, it says something that cheating services are so prominently featured by the likes of Google and Apple as education resources. While I understand that Google and Apple cannot tell the difference between cheating and “homework help,” and that they have no incentive to, I can only imagine the complication this adds to every academic exercise.

Student Uses Spy Glasses on College Entrance Exam

In Japan, a student has been criminally charged for attempting to use high-tech spy glasses during a college entrance exam.

According to the coverage, the student used glasses with an embedded camera, connected to a smart phone in his pocket. The camera sent images of test questions to “tutors” connected by his phone. Answers were sent back to the student in real time, or in time enough to answer.

Remember, Chegg and other answer-on-demand services will answer questions sent by camera phones. I am not saying Chegg played a role here. The “tutors” were not identified in the story. I am saying that it’s pretty easy to get people to cheat for you with just your camera.

The school filed criminal charges, the story says, specifically to “deter future cheating attempts.” The story also says:

Local prosecutors will decide on potential charges. [The school], for its part, says it will "respond harshly" to maintain fair testing environments.

I am not for young students facing jail time or hard criminal punishments for cheating. Though cheating is not a victimless crime. And good for the school for realizing that how you handle today’s cheaters has an impact on future attempts. Examples matter.