Faculty in University of California System Overwhelmingly Say Cheating Increased During Remote Classes

Plus, Inside Higher Ed runs two articles on cheating. Plus, Quick Bites.

Issue 58

Instructors in the University of California System: Cheating Was More Common in Remote Classes

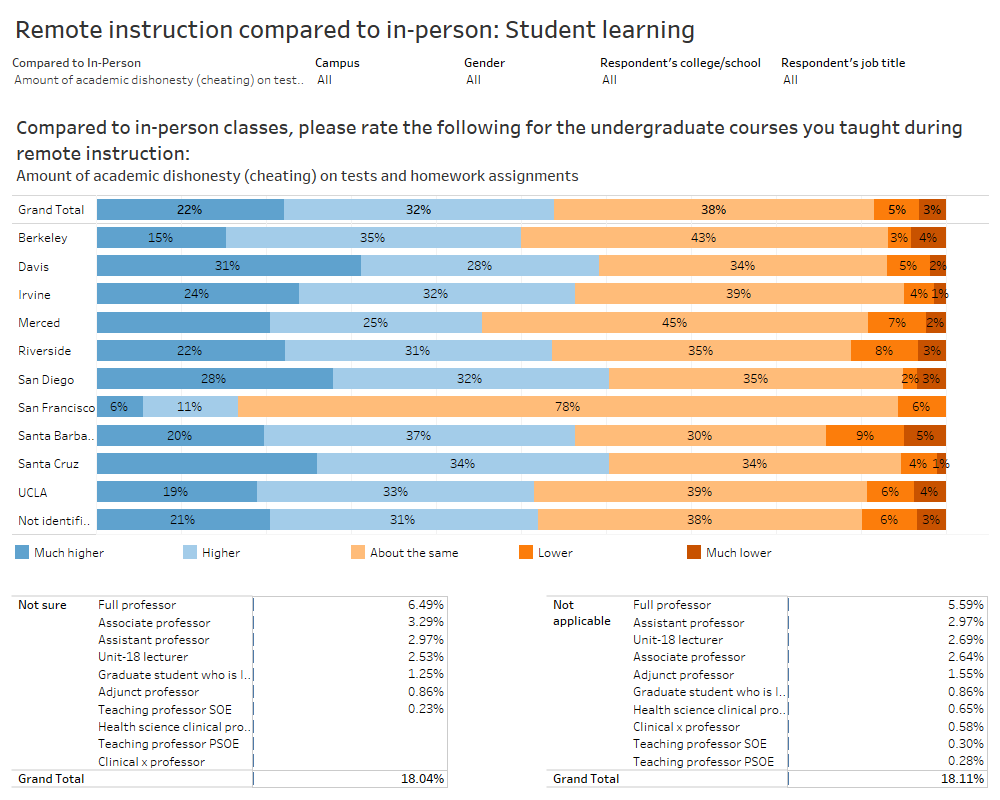

By a whopping margin of 54% to 8%, instructors and faculty in the University of California system said that the “Amount of academic dishonesty (cheating) on tests and homework assignments” was either “much higher” or “higher” during remote instruction compared to “in-person” methods.

First, a round of applause to the Cal system for asking about misconduct and for releasing the results - even breaking them down by campus.

The results are from a survey of more than 4,300 teaching staff, conducted May through June of this year.

And, if you’re paying attention, the results are not surprising. The preponderance of research has shown that cheating is more common in remote or online classes and an avalanche of contemporary reporting has shown a dramatic, often multi-fold increase in reported misconduct in the past year and a half.

When teachers are saying - by a 7:1 margin - that cheating is more common in online classes, maybe it’s time to believe that it is.

Inside Higher Ed Publishes An Article on Cheating

After partnering with and promoting cheating company Course Hero (see Issue 40) and absolutely butchering the most basic information on academic misconduct (see Issue 49), Insider Higher Ed (IHE) recently and surprisingly published an article on cheating - here.

It even acknowledges cheating exists and may be a problem, titled:

Is Cheating a Problem at Your Institution? Spoiler Alert: It Is

Yes, despite what IHE says, it is indeed.

The article, by David Rettinger of the University of Mary Washington and Kate McConnell of the Association of American Colleges and Universities, rests on the very debatable premise that it’s possible to teach or design a way around cheating.

Nonetheless, it is dead on when it says:

we believe academic misconduct is an existential threat to higher education. If we cannot assure that our students are doing authentic work, then we risk upending our value proposition to both students and society. The value of higher education depends on sending graduates into the world with the skills and knowledge we claim to be teaching and habits that prepare them to tackle the challenges that face our world. Unless we in higher education are able to ensure that the degrees we award actually reflect authentic learning, our place in society is in peril.

They add:

Many institutions worldwide address academic integrity using the ostrich method, preferring to keep our collective heads in the sand and respond only when confronted with an egregious incident that can no longer be ignored.

On these points, I agree completely.

And although the authors pivot from there to discounting efforts to detect and deter cheating, they do offer five suggestions for addressing it including “create policies and practices to address academic misconduct” and “develop a culture of integrity” and “incorporate authentic assessment strategies…” and so on.

The major issue with those suggestions is that there is not a college or university in the country that thinks they do not already do every one of those things. They have policies, they are proud of their “culture of integrity” and they encourage their instructors to use “authentic assessments.” Those are “the ostrich method.”

They are good suggestions and schools should absolutely heed them. And we should discuss whether schools are doing them well or enough - spoiler alert, they are not. But we should also acknowledge that these strategies are not enough to deal with “an existential threat to higher education,” as Rettinger and McConnell correctly diagnose.

Inside Higher Ed Publishes An(other) Article on Cheating

After partnering with and promoting cheating company Course Hero (see Issue 40) and absolutely butchering the most basic information on academic misconduct (see Issue 49), Insider Higher Ed (IHE) recently and surprisingly published an article on cheating - here.

This piece is by Jonathan M. Golding, a professor at the University of Kentucky and it’s on ways professors may prevent student cheating “via online apps.”

What the professor describes is collusion cheating in messenger apps - private chats that students use to share test or assignment questions and answers. It’s very common and very hard to catch, though there are ways to do it. See Issue 20 for an example.

The professor says:

Several months ago, I gave the first exam in an online course. Following the exam, I received an email from a student who told me that many of their classmates -- ultimately 35 students out of 270 -- had posted screenshots of the exam to a GroupMe. Not only were students sending screenshots of exam questions to their peers, but they were constantly discussing questions on the exam. If that student hadn’t contacted me, I probably would never have known about the cheating.

True. And since the 35 were using just that single collusion app, and there are hundreds of them, it’s likely that far more students were involved. In any case, he continued:

I also kept in mind that depending on students not to cheat due to an honor code or statements in a syllabus was probably going to be a losing battle, based on years of research on college cheating.

Also true.

To deal with the collusion challenges, Professor Golding makes a few suggestions including giving graded material in person instead of online. Check. Reducing the amount of time students have to start or complete online assignments. Check. Developing a question bank so students do not get the exact same tests. Check.

But then he says, to combat collusion cheating, instructors should:

not rely on software that blocks students from accessing the internet on their computer during exams, quizzes or homework. Similarly, don’t count on software that records students’ movements when graded material is presented.

I’m sorry, what?

To try to explain, the professor says:

Internet-blocking software will not stop students from accessing online groups using other electronic devices. In addition, video may show students looking around or accessing those other devices, but in most cases, you will need to take the time to watch recordings of your students, and even then, it may still be difficult to determine whether someone was using another device to access a group and cheat.

It’s Stefani time. That is bananas - b-a-n-a-n-a-s.

According to the professor, you should not rely on video proctoring that “may show students looking around or accessing those other devices” during a test because “you will need to take time to watch recordings.”

Is he serious?

Never mind that, in suggesting in-person testing, he says, “the possibility of students cheating using online apps will very likely increase when students are out of your sight.” He does not recommend watching students take online tests.

It’s also clear that he does not understand how those systems work - they do indeed check for student access to cell phones and secondary devices and can even stop an exam if a student uses one.

Even so, he suggests instructors not use a tool he acknowledges can show students cheating because it’s more work and “it can be difficult to tell” if someone who was on their cell during a test was actually cheating.

“The Cheat Sheet” Quick Bites

The student paper at Rowan University (NJ) has a student piece looking at the types of cheating and why students should not do them.

Virginia Commonwealth University’s student paper reports on the “dramatic increase” in academic misconduct cases there, a take off on the school’s inclusion in a recent NPR story on cheating (see Issue 50). New: the story says 73% of reported students were found “responsible.”

According to reporting there, students at The University of Virginia, an honor code school, are considering changes that would generally lower the penalties for violations.

University of South Florida has announced a switch in remote proctoring providers from Proctorio to Honor Lock.

A half dozen folks in India were arrested for selling $8,000, Bluetooth wired flip flops and hidden ear pieces to cheat on national exams. Yes, arrested. Yes, flip flops. Coverage in India Times has photos.

Speaking of India, a state there reportedly shut down Internet access for 25 million people to stop exam cheating. They take it that seriously.

The Australian Academic Integrity Forum 2021 has released its list of speakers for the October 19 event. Details here.

Reminder, the International Center for Academic Integrity has a Day of Action on contract cheating on October 20. Details are here.

In the next “The Cheat Sheet” - That bizarre story on cheating that should never have been written. Plus, more sneaky essay mill advertising. Plus, faculty at the University of Central Michigan debate changes to academic integrity policies.

Thank you for sharing and subscribing with the links below: