Cheating is "Boomtime" for Some Students

Plus, don't be so quick to toss exams aside. Plus, even more trouble brewing for Chegg.

Issue 77

To subscribe to “The Cheat Sheet:”

To share “The Cheat Sheet:”

There’s no audio of my velvety voice doing “The Cheat Sheet” this time and there’ll be no Thursday Issue this week either - both for the same reason. I’m hosting a panel later in the week on lifelong learning and workforce education at the WISE Summit in Doha, Qatar, and there just isn’t time. I know you’ll be lost and despondent and I am sorry.

But, “The Cheat Sheet” will return next Tuesday, December 14.

Cheating is “Boomtime”

University World News carried an opinion piece recently from Dr. Jon Mason and Dr. Guzyal Hill of Charles Darwin University in Australia. The headline is spot on, “Cheating at university is boomtime for some students.”

The pair share with readers that, among the challenges of online learning, is “the growth of online services that help students cheat.” They say:

using the services of someone else to prepare assignments or sit exams, has become a full-blown industry now and is commonly referred to as contract cheating. The systems and protocols for achieving this have also become smarter, leaving plagiarism software behind the curve.

They also write:

Our research shows a spike in provision of services following the rapid transition to digital delivery that many institutions have had to navigate.

I’ll dive into their research in the future. But highlighting the big-picture, the big stakes of cheating, they say:

It is not just a question of cheating the system to get a credential. There are consequences to the student, university, profession and wider community. What if a nurse rostered to look after you in a life-threatening illness managed to avoid learning the detailed protocols necessary? Or a structural engineer skipped on learning the theory of stability and dynamics? What if a lawyer you are paying does not know the remedies in contract law? Choose any industry and ask a similar question.

Exactly. Cheating isn’t just about doing right or cutting corners. It’s an issue of safety, and trust in institutions.

Their piece is also noteworthy for their take on what some academic leaders are calling “authentic assessments” - the more subjective written or project work that is believed to be an antidote to cheating. It’s a terrible name.

Nonetheless, Mason and Hill, having looked at contract cheating providers, wonder whether those “authentic assessments” are part of the problem:

Have assessment practices reliant on written work and non-invigilated exams run their course? How can assessment practices be recalibrated so that integrity and character are back in the picture?

Continuing:

related research has already shown that the inclusion of oral presentations, a return to in-person invigilation and ‘completed-in-class’ assessments will be part of the solution.

When exams are not proctored (non-invigilated), they invite cheating. Written and project-based work is likewise just as susceptible to cheating. Mason and Hill are right that the best way to prevent misconduct is to close the gap between student and teacher, bringing assessments in class, in person or at least in view of a proctor.

Professors: Don’t Be So Quick to Toss Out Proctored Exams

Continuing their outstanding coverage of academic integrity and assessment, Times Higher Ed (THE) ran an article recently from two professors at Nottingham Trent University (England) - Andy Grayson and Richard Trigg.

They make the rare but welcome case that proctored (invigilated) exams that test students on their acquired knowledge are important and should not be discarded in a rush to address misconduct or embrace “authentic assessments,” though they don’t use that term specifically.

Grayson and Grigg say:

Invigilated [proctored] exams have an important role to play in the assessment diet of many courses.

They add:

At the simplest level, in-person examinations are one of the best ways we have of ensuring that the work submitted is genuinely the work of the student themselves.

The two also cite the threat that essay mills pose to the submission of written work. And spend a good deal of space arguing for the pedagogy of exams - proctored exams - saying:

people often need to be able to show knowledge and understanding of an area without looking stuff up in a book. Therefore, it is legitimate to test the extent to which a student is capable of doing this. Exams provide an estimate of the student’s ability to marshal a body of knowledge “at run time” in the absence of support from sources of information.

It’s not a question as to whether one type of assessment is open to cheating and which is not. Cheating can happen on every type of assessment. It’s not realistic to think you’re thwarting essay mills by giving an exam. Or thwarting cheating by making that test an open-book assessment. Or by assigning a written project or essay in place of an exam. They are all cheatable, and pretty easily.

More Legal Problems for Chegg?

Cheating provider Chegg, already facing a potentially serious legal challenge to its business model of selling answers (see Issue 57), may now face another challenge - this time from upset investors.

According to a news release from the law firm of Bragar, Eagel & Squire, “a nationally recognized stockholder rights law firm,” the company is investigating Chegg on behalf of stockholders. At the core of the inquest are statements made by Chegg leaders related to the company’s massive recent valuation losses (see Issue 68).

These types of shareholder challenges or threats are pretty common when major changes happen with public companies.

But that does not mean the challenge is misplaced. As I wrote previously in Issue 68 linked above, the idea that Chegg’s massive revenue and valuation drops are tied to declines in enrollments - as the company claimed - is pure nonsense.

Speaking of Chegg, They’re Still Talking

In Issue 64, I’d noted that Chegg had strangely started trying to buy course materials from professors for obscene prices, speculating that it may be related to their pending legal troubles over copyright misuse.

Well, they’re still at it. And quite clumsily.

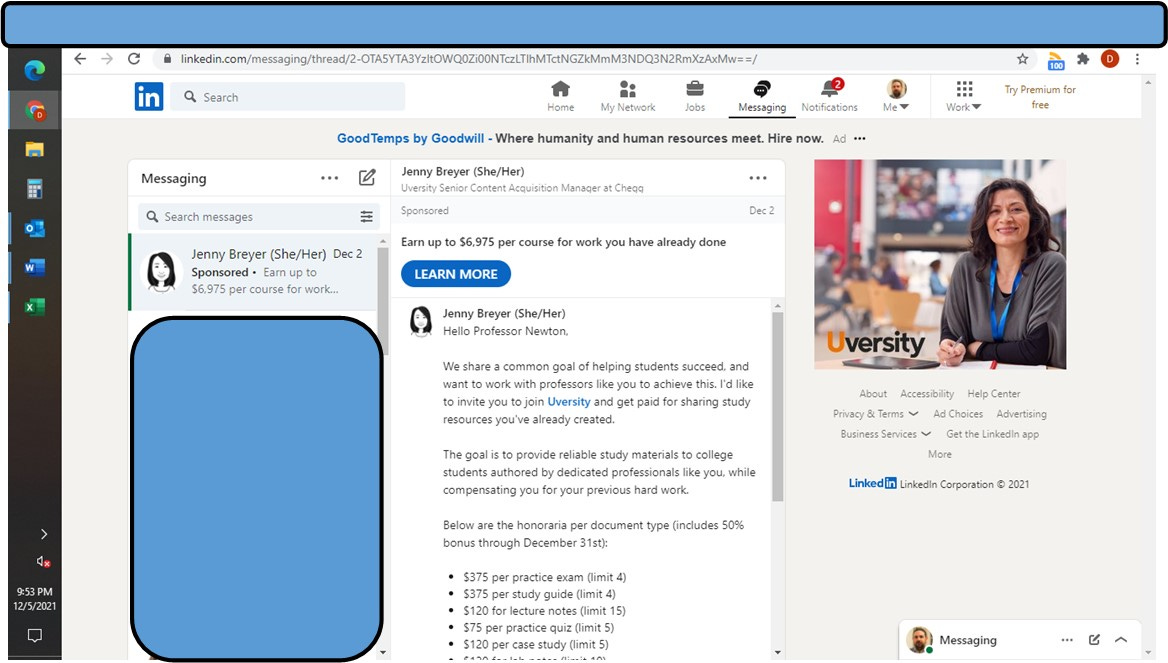

Here’s a screenshot of a paid message I received on LinkedIn:

Also as noted before, Chegg once again thinks I’m a professor, which I am not. It’s just so strange.

But what’s embarrassing about what their doing is that image on the ad - the one on the right - it’s stock art. Just google “image of teacher” and there she is on Shutterstock:

Seriously. The “education company” Chegg can’t find a real teacher to put in their ads? Not one? I guess that says just about everything.