394: OpenAI Usage Plummets in the Summer, When Students Aren't Cheating

Plus, another study shows AI detection works, and incredibly well. Plus, prospective medical students in Belgium sue, alleging cheating. Plus, Retraction Watch.

Issue 394

Subscribe below to join 4,871 (+1) other smart people who get “The Cheat Sheet.” New Issues every Tuesday and Thursday.

The Cheat Sheet is free. Although, patronage through paid subscriptions is what makes this newsletter possible. Individual subscriptions start at $8 a month ($80 annual), and institutional or corporate subscriptions are $250 a year. You can also support The Cheat Sheet by giving through Patreon.

OpenAI Usage Plummets in the Summer, When Students Aren't Cheating on Homework

According to data in this reporting, queries to OpenAI/ChatGPT significantly decline in the summer, the traditional breaks from school. The headline above is the headline on the article.

The outlet, Futurism, has not always done good reporting on integrity issues (see Issue 217). But they get the heart of the story right this time.

Usage of ChatGPT declines in summer. This is not news, (see Issue 248), but it is worth repeating. And it’s (part of) the reason I’ve been comfortable declaring OpenAI a cheating provider. Most of the other reasons orbit around the company’s decisions to not address, indeed actively resist, any activity that would make ChatGPT less easy to use for fraud.

Anyway, to the coverage. Futurism writes:

as students of all ages grow to depend on AI to do their thinking for them, it seems AI companies also depend on students to make up a staggering proportion of their user base.

Yup.

And:

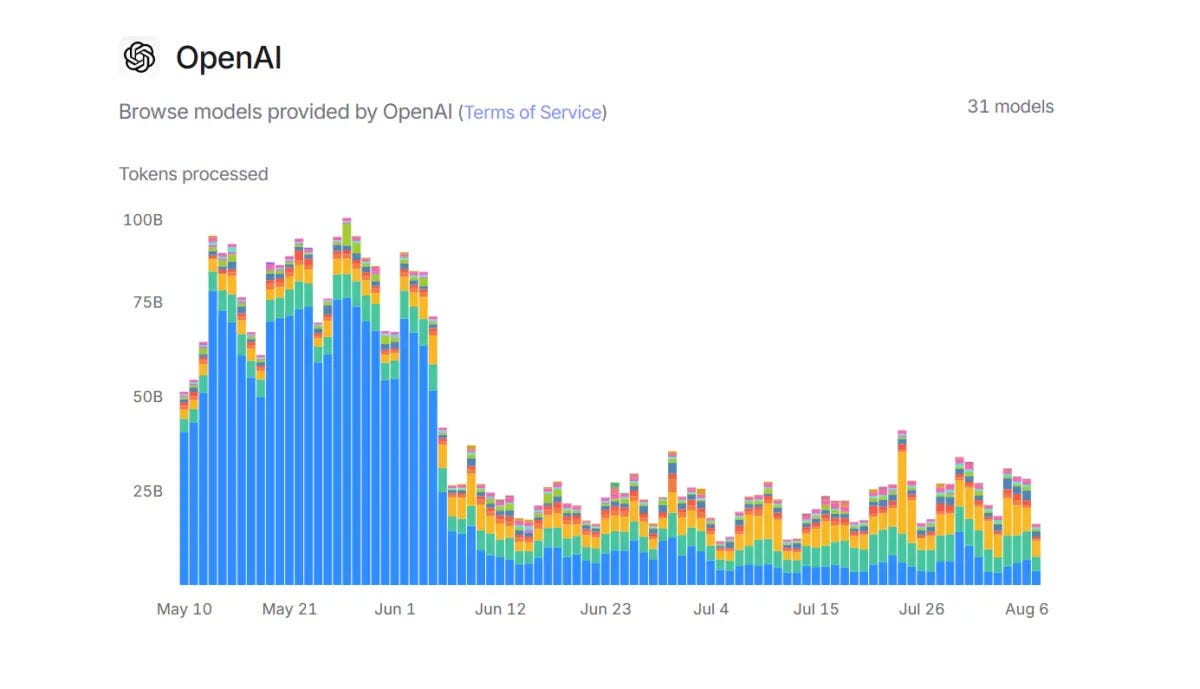

Data recently released by AI platform OpenRouter, a "one stop shop" for interacting with the medley of AI models on the market, shows a steep drop-off in ChatGPT queries from late May, when the school year is still in swing, to early June, when schools let out.

Imagine that.

Also:

Taken together, the daily stats show that ChatGPT usage hit its peak on May 27, when users generated 97.4 billion tokens — a unit of measurement for data processed by an AI system that OpenAI says is equivalent of about four English characters — in a single day, right during finals season.

In May, ChatGPT users generated an average of 79.6 billion tokens per day — compared to 36.7 billion for the same period in June, when schools typically let out. OpenRouter's graph of the data speaks volumes:

And:

Interestingly, there were some dips during the school year as well — which just so happened to line up with weekends.

You don’t say.

There’s also this:

earlier this year, an in-depth study of 10,000 ChatGPT prompts by scholars at Rutgers found that student interactions with the bot strongly correlated with their school calendar. Spring break and summer were particular dead zones, leading the team to conclude that "most usage was academic."

I had not seen that study. I left the link in, should you want to check it out. But “most usage was academic.” Again — you don’t say. If you watched OpenAI/ChatGPT closely enough, that was easy to tell.

Research: AI Detection Works “Remarkably Well” and “Results are Clear-Cut”

A new research paper from Brian Jabarian and Alex Imas, both from the University of Chicago, Booth School of Business, shows — yet again — that good AI detection systems work and work incredibly well.

I lost count, but this must be the third or fourth separate paper showing the same thing. For two, see Issue 253, or Issue 367.

Importantly, it’s possible, albeit misleading, to lump all AI detection systems together, average their results and declare them to not work (see Issue 250). But if you care to research good systems, as this new paper has, you’ll find they work to near perfection. In fact, even the papers that claim the opposite actually show very high accuracy rates for the reputable solutions. They just bury those results with averages of lousy ones. As far as I know, no research anywhere has shown that the quality AI detection systems don’t work.

Before getting into what it says, there are a few things to like about this paper. To start, as alluded to above, the researchers didn’t screw around with the junk. They tested one “open-source” detection system —RoBERTa — and three commercial systems — GTPZero, OriginalityAI, and Pangram. Further, this paper does not issue results for a class, it courageously scores each system.

I also like that in addition to testing and scoring these technologies on a large battery of diverse texts and AI-creation models, the researchers also tested these systems against a popular “humanizer” — shameful tools designed, or at least sold, specifically to bypass AI detection. That is, they’re designed/sold to help people misrepresent things without risk.

Anyway, I like this because one of the things the anti-AI-detection chorus says is that detection does not work because it’s easy to bypass, even though those are different things. So, let’s see what happens when “humanizer” text is run against credible detection.

I don’t like that this paper did not test Turnitin, probably the best-known and most-used detection system. I don’t know whether that lies with the research team or with Turnitin. If the team asked to test Turnitin and was denied, I would have loved to see a research note. Maybe they did not ask. Either way, it’s important data that would be helpful to have.

Enough preamble.

But — sorry — one more note. If you’re not up on the terms of science, FPR is false positive rate. That’s the rate at which a detector finds text to be AI-generated, but it was, in fact, human-created. FNR is false negative rate — the rate at which a detector finds text as human-written when it was created by AI. Collectively, the FPR and FNR convey accuracy. In academic settings, most people are far more concerned about FPR than anything else.

From the paper:

we find that detectors vary in their capacity to minimize FNR and FPR, with the commercial detectors outperforming open-source. Second, most commercial AI detectors perform remarkably well, with Pangram in particular achieving a near zero FPR and FNR within our set of stimuli; these results are stable across AI models.

Most commercial AI detectors perform remarkably well. Just underlining.

Across all tests, Pangram was the most accurate, the paper found:

The results are clear-cut. Pangram stands out as the only AI detector maintaining policy-grade levels on our main metrics when evaluated on all four generative AI models. On medium-length to long passages, Pangram achieves essentially zero FPRs and FNRs within our sample

Essentially zero FPR and FNR. Underlining again.

Although Pangram ran the table in terms of accuracy, the two other commercial providers scored well too:

The other two commercial detectors, Originality.AI and GPTZero, perform well on long and medium length texts, but, depending on the detector, struggle on short and ‘humanized’ passages. The open-source RoBERTa baseline both misclassifies human-written texts and fails to identify up to 51% of AI-generated passages.

Since I brought in the humanizer there, once again, Pangram caught that:

Importantly, Pangram’s FNR is robust to the use of current “humanizers”; the FNR remains low even when AI-generated passages are modified using tools such as StealthGPT. OriginalityAI and GPTZero constitute a secondary tier with partial strengths, making the choice between the two dependent on the user’s priority

More:

we find that Pangram is the only detector that meets stringent policy requirements without compromising the ability to detect AI text, while OriginalityAI comes second

And:

Pangram emerges as the most cautious detector. Pangram achieves a zero FPR on longer passages and essentially a zero FPR on medium passages. The FPR increases a bit on shorter passages, but never rises above 0.01. Both GPTZero and OriginalityAI keep the FPR at 0.01 or below on medium to long passages and below 0.03 on shorter passages

This is not the first time either that Pangram has been singled out in research about accuracy (see Issue 390).

One more blurb on the “humanizer” test, since I know people care about this:

Since the goal of humanizers is to avoid detection, the relevant statistic is the FNR. Pangram’s performance is largely robust to the humanizer. For longer passages, Pangram detects nearly 100% of AI-generated text. The FNR increases a bit as the passages get shorter, but still remains low. The other detectors are less robust to humanizers. The FNR for Originality.AI increases to around 0.05 for longer text, but can reach up to 0.21 for shorter text, depending on the genre and LLM model. GPTZero largely loses its capacity to detect AI-generated text, with FNR scores around 0.50 and above across most genres and LLM models.

In other words, at least this humanizer can degrade the odds of detection in some systems, but not all of them — verbum sapienti.

As justifiably giddy as Pangram probably is with these results, the bigger picture is really impossible to deny at this point. AI detection works.

I mean, what more do you want than a zero false positive rate and a zero false negative rate? For any detection regime, perfection is an absurd standard. But here, you’ve almost got it anyway.

My next question — which you knew was coming — when can we stop saying AI detection is unreliable? When will someone go back to the schools that have used reliability questions to deflect and rationalize their no-look policies about AI use? Such policies were never defensible and they’re becoming even less so with every single piece of evidence.

Students in Belgium Allege AI-Related Cheating on Medical School Entrance Exam, File Suit

According to news coverage from Belgium, a group of students has filed a legal challenge seeking an investigation to what they suspect was AI-cheating on recent medical school admissions exams.

The students:

argue that some candidates may have relied on AI-generated answers in the July 3–4 exam, which recorded an unusually high pass rate of 47% compared to 18.9% in 2024 and 36.7% in 2023.

I have no idea whether cheating went on during these tests, but those are some funky passage rates — 19, 37, and 47? Also, it is odd that it went down in 2024. If there was AI-assisted cheating, you’d expect to see it in 2024 as much as 2025. But what do I know?

More from the news coverage:

The exam appeals committee has so far refused to investigate large-scale cheating. At least five students are now turning to the civil court, which could either appoint an independent expert or compel the appeals body to launch its own inquiry.

[The lawyer for the students] said a proper investigation would track which websites candidates visited during the test and by whom, potentially reshuffling results and granting his clients entry to the program.

Again, I have no idea. But it would be quite surprising if the exam provider was not checking website visits during the test. It’s shocking that visiting outside websites was even allowed, if it was.

In case this is news — no one should be giving any kind of online assessment without strict security and integrity provisions, and supervision. And honestly, I’m not even sure that’s enough.

Retraction Watch

Academic fraud is not limited to students, not even close.

We’ve seen business and political leaders lie and misrepresent their academic achievements, even engaging in overt plagiarism. We’ve seen teachers, test proctors, and others help students cheat.

And unfortunately, our age of academic dishonesty has also permeated research and journal publishing, where educators and scientists use many of the same tactics that their students use — all with the aim to fudge, deceive, and accept credit for work that is, at best, inauthentic.

If you’re as disturbed by this as I am, I encourage you to check out, and subscribe to, Retraction Watch. Their work chronicling the dark deeds of academic publishing is heroic, and never receives enough credit. I am a fan.